|

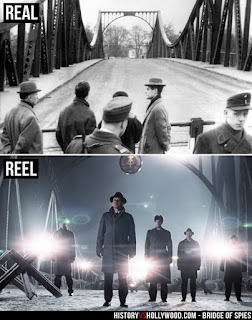

| Glienicke Bridge, Berlin, adapted for Bridge of Spies Photo by Biberbaer |

His father was a revolutionary exile from Tsarist Russia at the start of the 20th century, caught spreading Marxism in the company of Lenin himself, in St. Petersburg. A German by birth, Heinrich Fischer faced deportation back to his native country and either conscription or imprisonment. However, he was a skilled engineer and easily found work in the booming industrial North-East of England.

Not that Heinrich left his revolutionary ideals behind, and preached to British socialist groups in the area. He was even murkily involved in a plot to ship arms from Newcastle to rebels in Russia, but escaped conviction after his links to the group couldn't be established clearly enough. After exoneration, Fisher and his young family - Henry, born in 1902 and William, born in 1903 - moved to Whitley Bay, where the sons were enrolled at Whitley Bay & Monkseaton High School in 1914.

|

| The Fisher family in 1917, William at rear on left. From The Kremlin's Geordie Spy, Dr. Vin Arthey |

However, as post-war depression seized England and William's father Heinrich found it harder to keep working, he began considering a relocation to Lenin's Russia. His sons, nearing eighteen, seemed destined for university places he could never afford, and the possibility of revolution in England seemed less likely every day. By 1921, the Fishers were on their way to Moscow, now the capital of the Soviet Union, and William Fisher left behind his home in the North-East and Newcastle, for good.

The young William's life developed quickly in the new Russia. Tragedy struck first, when his brother Henry drowned late in the summer of 1921. The family fractured irreparably from this accident, and it formed in the developing William a quiet reticence that would mark him for the rest of his life.

His past is somewhat difficult to decipher, as befits an intelligence officer. It is stated that, like many young men in Russia, he was part of the Komsomol, the Red Army as a radio operator, and then the OGPU, the Russian state security organisation - which, after many years and changes of name, would become the dreaded KGB.

Academic and writer Dr. Vin Arthey, whose book The Kremlin's Geordie Spy inspired this article, includes an anecdote related to him by Fisher's daughter Evelyn about William's recruitment into the OGPU;

"In this document you say that you're German. Here you say you're Russian. Here British. What are you?"Indeed, by 1929 William had a wife, Yelena, and a daughter, as well as a brand new name for his Russian life - Vilyam Genrikhovich Fisher. He would begin to move about Western Europe, working within established communities of Soviet spies, often as their radio operator. Returning to Moscow in 1934, the OGPU became the NKVD and Fisher found himself training the next generation of spies in radio work - including the infamous Kitty Harris, lover and KGB contact for Donald Maclean of the "Cambridge Five".

Fisher replied, "I don't know what I am according to your rules. I'll be whatever you say I am."

"You're Russian."

Fisher narrowly dodged Stalin's purges from 1938, receiving only a dismissal instead of a bullet, but was reactivated for duty with the intelligence service in 1941 as Soviet Russia reeled from Nazi Germany's lightning invasion, with a dearth of skilled intelligence operatives after the Purge.

After the major battles of Stalingrad and Kursk turned the tide in favour of the Soviets, Fisher was involved in several successful operations, including the astounding Operation Berezino.

Certainly, Fisher emerged from the war unscathed and awarded the prestigious Order of the Red Banner. Powerful individuals high in Soviet state security took more notice of Fisher, and he received the most prestigious assignment for a Russian spy - North America.

From 1948, Fisher was to resurrect the 'Volunteer' network, which had smuggled atomic secrets out of Los Alamos during the war. Within the space of a year from Fisher's arrival, the Soviet Union detonated their own atomic bomb, a near-replica of the American design. Conversely, he dodged the fallout from the arrest and execution of the Rosenbergs in 1951, who confessed nothing and left the network more or less concealed.

It would be the enemy within that would ultimately bring down Fisher, however. An assistant was assigned by Moscow, Reino Häyhänen, who posed as a Finnish-American and joined Fisher in 1954. However, Häyhänen had none of the drive and self-control required by an intelligence operative, and was an abrasive drunk. The first message he received upon being assigned to Fisher's New York based network was concealed in a fake nickel, which he subsequently lost. It was discovered, a year later, when a paperboy dropped some change and the nickel cracked open.

|

| Colonel Rudolf Abel, aka William Fisher, arrested in 1957. From History vs. Hollywood |

Fisher, under interrogation, claimed his identity as Colonel Rudolf Abel, a very close friend; Fisher's motives for this new disguise were seen as a way of communicating his situation to his superiors in the KGB, without actually admitting to his real birth name of William Fisher. Sadly, Fisher had no idea the real Abel had passed away not long after Fisher's final mission to the US had begun.

This total unwillingness to supply any information to the Americans - even when offered reimbursement for defection - could have stymied the entire operation against him, leaving the US Government no legal place but to deport 'Abel' as an illegal alien and nothing more.

Nevertheless, with the alcoholic Häyhänenin the stand, testifying about Fisher's activities, there was sufficient grounds to bring charges of espionage against the United States. Going before a grand jury, the Bar Association had to appoint a lawyer for Abel's defence, as no-one would volunteer for the role.

They chose wisely it was seen, in the form of James B. Donovan, now an insurace lawyer but at one point had served as Assistant Prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials of 1946, and had also served as legal counsel to the Office of Strategic Services; he was eminently qualified to handle matters of espionage and law.

He was also an honorable man, determined to ensure his client received a fair trial under the requirements of the Constitution of the United States. Abel would be facing three charges

- Conspiracy to transmit defense information to the Soviet Union

- Conspiracy to obtain defense information

- Conspiracy to act in the United States as an agent of a foreign government without notification to the Secretary of State

"It is possible in the foreseeable future an American of equivalent rank will be captured by Soviet Russia or an ally; at such time an exchange of prisoners through diplomatic channels could be considered in the best interest of the United States."It was only a few years later, in 1960, when US pilot Francis Gary Powers was flying the high-altitude U2 spy plane over Sverdlovsk in the Soviet Union, seemingly out of range of Russian air defences. A missile in fact successfully crippled his aircraft, forcing Powers to bail out - right into the waiting hands of the Soviet security services. He too was put on trial, and sentenced to imprisonment on 19th August 1960.

The ground was laid for an exchange however; the American press were calling for a swap of Abel and Powers, the CIA began making plans as soon as Powers was shot down, and Donovan had been receiving messages of thanks from 'Mrs. Abel' in Leipzig, which the US intelligence services believed to be a cover for the KGB to communicate directly with them.

It was indeed, and for the next two years delicate diplomacy between Donovan and an East Berlin lawyer called Wolfgang Vogel led to an exchange on the Glienicke Bridge that linked the West and the East - in many ways.

Donovan stood with Abel, and across the bridge stood Ivan Shishkin, a member of the Soviet embassy to East Germany, with Powers. The two men crossed, the Russian spy and the American pilot, joined their former colleagues, and were both whisked away for intense debriefing. After many months of careful, utterly secret negotiation, the exchange had concluded flawlessly.

|

| Officials and guards await the prisoner exchange at Berlin's Glienicke

Bridge (top). Soviet officials arrive for the prisoner exchange in the Bridge of Spies movie. From History vs. Hollywood |

His health was deteriorating rapidly as well. He referred to his vice of smoking cigarettes as "coffin nails", a slang term he recalled from his childhood and teenage years on Tyneside, and by 1971 had been diagnosed with lung cancer. His final words to his daughter, Evelyn, came in English and were "Don't forget we're Germans". In his later, final and bitter years, it is accepted that Rudolf Abel, aka William Fisher, came to regret the career of a spy that estranged him from his family, his country, and even his name.

He died on 15th November, 1971, and his ashes were interned in Donskoi Cemetery in Moscow beneath a headstone inscribed with the name Rudolf Ivanovitch Abel. A year later, his widow Yelena successfully campaigned to have it changed to Vilyam Genrikhovich Fisher, before passing away herself in 1974. Their daughter Evelyn died in 2007.

So concludes the odd story of a boy from Benwell, who ended up shaking the world from Washington to Moscow via Berlin in one of the greatest spy stories of the Cold War.

I am deeply indebted to Dr. Vin Arthey for writing The Kremlin's Geordie Spy and for answering the questions that helped form this article. I asked him if William Fisher had ever expressed a desire to return to his childhood home in the North-East. Vin replied that he had not, and even if he had, it would have been far too dangerous. Such, it seems, are the prices paid by spies.

|

| The grave of Vilyam Genrikhovich Fisher Donskoi Cemetery From Find A Grave |